Do you really want my feedback?

Posted: December 3, 2018 Filed under: Change, Disruptive Behavior, Health and Care Radicals, Hope, Hospital, Leadership, Making a Difference, Patient, Patient Experience, speaking up | Tags: Feedback, Healthcare, Hospitals, Leadership, Patient Experience Leave a commentI had a routine GI procedure three weeks ago. You know the drill; “after the prep, the procedure is a piece of cake…”

That one!

I had a great experience. The results were clean and benign! The staff were friendly, the center was clean, the nurses were kind and professional and explained everything well. The doctor was personable and had an appropriate (enjoyable for me) sense of humor. Everything ran on time and my ‘competent adult’ escort got me home before lunch time – I was starving!

Life quickly returned to its ‘pre-prep’ normalcy and the procedure was a distant memory. Or so I thought…

This morning a 37-question paper survey arrived in our mail box, asking me to share my “thoughts and feelings”.

My immediate reaction of wanting to recycle this piece of ‘junk mail’ was curtailed by my morbid curiosity to re-examine this antiquated and ineffective means of gathering feedback.

Do our hospital and health system leaders really believe that this is an effective way to gather feedback about my experience of the care that I received? I can’t remember what I had for breakfast this morning and you’re asking me to rate the “Attractiveness of the Surgery Center” from three weeks ago.

This is absurd on so many levels!

I really don’t recall how attractive the surgery center was, nor do I really care.

I care that your staff were kind, compassionate and didn’t keep me waiting. I care that you knew who I was and did the correct procedure on me. I care that you explained what you were doing to me and that you all seem to know what each other was doing, apparently enjoyed working together, had the equipment to do your jobs safely and effectively and seemed to be committed to taking care of me as a priority.

Listen. If you really want my feedback, if you really want to know my thoughts and feelings, do what our vet does after my dogs have a visit; call me that night or the next morning. If I’m not available chat with my wife (she was the competent adult that picked me up…), trust me, she will know whether my experience with you, your facility and your caregivers was anything other than stellar.

This would also allow you to determine whether I was suffering any post-procedure discomfort or pain. That call would also be an appropriate time to ask me whether I had any questions about the procedure and you could remind me about any follow up that I needed to remember.

If you can’t afford the time for a person to make a call, then send me a text or an email with half a dozen quick questions. In fact, that might be better, then you’d have the real time data to inform any changes to your operations or any service recovery for your patients.

The 80’s called, they would like their survey back!

We can do better than this, our patients and caregivers deserve better than this!

P.s. send the pager and fax machine back too…

The Secret Sits

Posted: June 11, 2018 Filed under: Change, Health and Care Radicals, Hope, Hospital, Leadership, Learning, Patient, Patient Experience, Personal Accountability, Safety, Uncategorized | Tags: Accountability, culture of safety, data, Experience, Healthcare, hospital safety, Hospitals, improvement, Leadership, measurement, Patient Experience, patient safety, Patients Leave a commentI recently used Robert Frost’s poem “The Secret Sits” as a blog writing prompt…

“We dance round in a ring and suppose,

But the Secret sits in the middle and knows.”

In the blog I suggest that much of what we do as leaders in healthcare (the dance) and what we measure in healthcare are disconnected from what our patients and staff really want and need (the secret sitting in the middle).

I was recently in a hospital conference room preparing for a leadership meeting; the walls were papered from floor to ceiling with graphs, tables and charts… a “loud” visual statement that a myriad aspect of operations was being measured and reported. During our meetings I dug a little deeper, listened to the leaders, caregivers and patients, and then looked a little closer at the “scores” on the walls.

Outcomes, as measured and reported, apparently hadn’t changed much over the past two-years… It was not lost on me either that this conference room that is billed as the “control-center” of operations felt lifeless and soulless… For an organization committed to ‘health’ and ‘care’, this felt like a disconnect.

And I’ve seen hospitals that are listening to the “secret”. They are measuring, reacting and acting differently. They are breathing life into their data and working on ways to make it as real-time as the work and care that it is intended to measure. Outcomes are improving, care is safer and the experience of those caring and being cared for is markedly improved; so I am optimistic and incredibly hopeful that we can rethink what we measure and how we act. How we lead.

Check out my blog “Improving the Experience of Care” (first in a two-part series) on our company’s site. I’d love your thoughts, comments and ideas:

- Are we measuring the right things in healthcare?

- Is chasing an improved CAHPS score, or a better CMS Star Rating, the right way to drive change?

- Can we measure everything that matters?

- How do you measure a healthy, effective and respectful culture?

- What’s the secret that you’re dancing around?

Improving the Experience of Care – let’s start with our words.

Posted: March 17, 2017 Filed under: Accountability, Audactity, Change, Hope, Hospital, Host, Patient Experience, Workplace Culture | Tags: Experience, Healthcare, Hospitality, Hospitals, Patients 4 Comments

I recently re-read the words of broadcast journalist Walter Cronkite, “America’s healthcare system is neither healthy, caring, nor a system.”

This sad and yet truthful reflection, combined with the reality that our founding partner, mentor, friend, student of the classics, and therefore a natural etymologist – Tim Sullivan – had me thinking about the origination of the words we use in healthcare.

Two words in particular; hospital and patient.

A quick scan of history reveals that in the middle ages hospitals were in fact almshouses for the poor, or hostels for pilgrims. The word ‘hospital’ comes from the Latin word hospes, meaning an entertainer, host, a visitor, a guest, a friend bound by the ties of hospitality.

Another noun derived from this is hospitum which came to mean hospitality, or the relationship between guest and shelterer. Hospes is also the root of the English word host.

In my travels, I have witnessed many hospital leaders who have lost sight of the fact that our roots go back to providing shelter for the poor, a resting place for those on pilgrimage, and completely lost sight of the tenets of welcoming patients as guest or friend.

The English noun ‘patient’ comes from the Latin word patiens, the present participle of the verb, patior, meaning ‘I am suffering’.

The hospital should be a place of respite for the friend that is suffering.

I think it is fair to say that if you’re leading in a hospital (regardless of size) you’re contributing to the running of one of the oldest aspects of the “service industry”. Yet at many hospitals, we seem to have left the consistent delivery of this ‘service’ completely up to chance or in the care of those without the training and skills necessary to deliver upon the promise.

Service – from the old English meaning religious devotion or a form of liturgy, from old French servise or Latin servitium ‘slavery,’ from servus ‘slave.’ The early sense of the verb (mid-19th century) was ‘be of service to’, or ‘to provide with a service.’

What service is your institution providing those who are suffering that come to your hospital for care and cure?

Do you insist on telling your patients and communities why they should be satisfied with your ‘service’ because of how safe you are, what good ratings you get, or how qualified your staff are?

Or are you listening to those you are called to serve in order that you might better deliver the service(s) they need?

Your patients want to feel welcome, be treated kindly, understood, healed, cured, communicated with (not to), and they don’t want their time to be wasted.

The rest (the safety, the expertise and the qualifications) are a prerequisite – foundational and non-negotiable.

Are you listening to those you serve?

Leadership Lessons from Mike Dowling

Posted: January 26, 2015 Filed under: Accountability, Change, Leadership, Learning, Love, Making a Difference, Personal Accountability | Tags: Accountability, Clarity, Communication, Healthcare, Leadership, Lessons learned Leave a commentLast speaker of the day

Several years ago I found myself in the audience of a quality and safety conference at Harvard University. The last speaker of the day took the podium with little fanfare and no slides. What a welcome change…

With his very generous permission I’d like to share my memories and notes from that day, the lessons and leadership “keys” he shared then, ring true now, and continue to resonate with me.

Thanks Mike!

And now for something completely different…

Mike Dowling is the President and CEO of the North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System (NSLIJHS). Prior to becoming president and CEO on January 1, 2002, Dowling was the health system’s executive vice president and chief operating officer.

Mike served in New York State government for 12 years, including seven years as state director of Health, Education and Human Services and deputy secretary to former governor Mario Cuomo. He was also commissioner of the New York State Department of Social Services. Before his public service career, Dowling was a professor of social policy and assistant dean at the Fordham University Graduate School of Social Services and director of the Fordham campus in Westchester County.

Mike presented at the Eleventh Quality and Safety Colloquium (Cambridge MA – August 14-16, 2012) – my notes summarize his comments. Without any slides, Mike shared “7 Keys” to creating a “Premiere Healthcare Organization” by stating, “NSLIJ is not there yet, but we are on a journey toward this, and I’d like to share it with you…

Have a coherent idea of where you want to end up – a clear VISION

- Not just the “what” but the “why”

- You must be able to engage EVERYONE’S head and heart in the VISION – in the “why…”

Have a positive attitude

- Be optimistic and believe that it is possible – a “can do” attitude

- Be responsible for outcomes and model personal accountability – “if it is to be it is up to me”

Have a complete commitment to transformation

- Be ready to think differently – we CANNOT be risk averse

- Be open minded – healthcare is NOT unique – exceptional, high-quality organizations are NOT industry specific

Engage and develop EVERYONE

- Lead a continuous culture of learning

- Be mindful of who you hire, who you promote, who you let go

- Remember: People + Values + Behaviors = SUCCESS

- Use simulation

- Make a core part of your curriculum mandatory

Manage Constituencies

- Break down silos and train people across disciplines

- Manage your board and medical staff

- Change how we do medical school training

Become deeply consumer focused

- Everyone you serve is more educated and informed than ever

- Expectations are constantly changing

COMMUNCIATION

- Constant communication of the “why” from #1

- Top down, bottom up, side to side

- Face to face, electronic, multi-media, print, etc. etc.

- You CANNOT over-communicate

Most of all – remember that:

- we do great work every day in healthcare!

- we have much to be proud of!

- we do make a difference!

Mike closed his remarks with the words of Sir Winston Churchill, “Success is going from failure to failure without losing enthusiasm…”

Thank you Mike, you continue to inspire and encourage!

Pecha Kucha comes to IHI 26 Forum

Posted: December 11, 2014 Filed under: Change, Disruptive Behavior, Health and Care Radicals, Heretic, Leadership, Making a Difference, Pecha Kucha, Personal Accountability | Tags: Accountability, brave, culture of safety, Healthcare, Leadership, patient safety, speaking up, taking risks Leave a commentPecha Kucha!

“Bless you!” were the first words out of my mouth when I heard someone say peachakoocha during this week’s 26th annual Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Forum in Orlando, FL. On hearing the word, my 12-year-old daughter thinks it sounds like the name of a Pokemon character…

Weird word = wonderful experience

In a conference environment that can be all too often filled with long-winded PowerPoint presentations with presenters reading slides, this was an energizing and welcome change.

“PEH–cha KOO-cha,’’ is the English pronunciation, of what appears to be a rough translation of the Japanese word(s) for “chit chat’’. Picture an event akin to a poetry slam. A Pecha Kucha is where subject matter experts get together to share their work, opinions and beliefs, and get to hear from others. A fast paced opportunity to share, learn and be inspired.

Pecha Kucha started in 2003 in Tokyo and has since migrated to almost every country in the world. Originally designed to share ideas in design, architecture and photography, it has apparently now come to healthcare. There are now Pecha Kucha ‘nights’ in more than 300 cities around the world.

How does this work?

The Pecha Kucha at this weeks IHI meeting was hosted by Helen Bevan, Chief Transformation Officer for NHS Horizons Group (UK) who acted as host and ‘race marshal’. She explained to the audience what would happen, then welcomed each presenter to the podium, and then asked, “are you ready?”, setting their slides running for the ensuing sub seven minute presentation (6 minutes, 40 seconds)…

Presenters — there were 8 of them at the IHI — shared and narrated 20 slides for 20 seconds that “auto-ran”, meaning the presenter had no control over slide advancement, the slides roll…

The 20 x 20 format is at the core of a Pecha Kucha. The emphasis here is on speed! Can’t keep up, then you’re likely not ready for this rapid fire onslaught of ideas and inspiration.

What we witnessed at the IHI Forum was a Pecha Kucha focused on the theme of “my hope for the future of healthcare”. These were inspiring stories of why each presenter had been called to make a difference in healthcare and provided insights into specific projects that each of them were working on. Beautifully inspiring, brave, personal stories of commitments to lean in and make health and care safer, more accessible and more relationship driven; the triple aim is alive, well and thriving!

A refreshing change at a terrific conference. I commend Helen for leading this and congratulate the IHI for welcoming this imitation of a clearly different approach to sharing, learning and inspiring.

I’m a Pecha Kucha fan!

Check out this Pecha Kucha Storify

Personal Accountability

Posted: November 21, 2014 Filed under: Accountability, Change, Leadership, Learning, Personal Accountability, Trust, Workplace Culture | Tags: Accountability, Clarity, Communication, culture of safety, Healthcare, Leadership, Lessons learned, speaking up 2 CommentsA conversation with Chuck Lauer

Last year I had the wonderful opportunity to be introduced to Chuck Lauer, the former publisher of Modern Healthcare, by my good friend and colleague Kristi Peterson. Chuck and I spent considerable time talking and emailing about a subject of mutual interest and something we are both passionate about, accountability, specifically about the idea and concept of ‘personal accountability’.

This concept of personal accountability, and the choice to change the words I use when I think about accountability, are in part lessons from the leadership, writings, and friendship of Linda Galindo.

Chuck went on to pen a piece that appeared in Beckers Hospital Review on August 17th 2013. I just re-read it, and thought I’d share it here again. Enjoy…

We hear a lot about “accountability” in healthcare — from the boardroom, to the workplace, to new payment methodologies like “accountable care organizations” — but most people don’t have a clue about what the word really means.

Everyone knows the basic definition: Accountability is a kind of answerability. The word derives from having to give an account — to clearly explain what you are doing. But the actual definition goes much deeper than that.

Richard Corder, assistant vice president of CRICO, a Harvard-affiliated malpractice and patient safety organization, has thought a lot about what accountability is — including what it is not. It is not, he told me recently in an email, about saying “yes” whenever your approval is sought. “In healthcare, we have fallen for the belief that good service means saying yes to everything,” he said to me. “Saying no — and being clear about why, and when you may be able to meet, chat, review, discuss — is a liberating, time-saving, accountable action.”

One of the things often missing in today’s workplace, he said, is a lack of clarity about what accountability really means. “Treating everyone the same is disrespectful to our high performers and excuses (rewards) our middle and low performers,” he said. Fairness is not about treating everyone the same. As leaders, we understand that we have to treat, manage, coach and lead people differently — based upon performance and needs.

“In healthcare, we are currently spending a lot of time (and money) talking about and pondering the ‘accountable entity,'” he told me. “We wax and wane poetically about the who, what, why, when and where, when all the time it’s staring back from the mirror. We are the accountable entities.”

That gets us to the heart of the matter: Accountability has to start with you! If you are ever going to be successful and fulfilled in your life, you have to be accountable to yourself. Sure, you can kid yourself about how good you are, and you can even fool other people by what you say and how you behave. But do not forget that the hardest person to satisfy is you! You have to judge yourself and live with it every day!

Each of us is an accountable entity. That’s why, when leaders lead with clarity and conviction, honesty and transparency, they bring with them inspiration and determination. They have become accountable to themselves! It’s a contagious enthusiasm that permeates their organizations. Talented people are attracted to institutions where leaders are dedicated to innovation, creativity and risk-taking. They fully accept that answering to oneself is the key to success.

I have had the honor of meeting a lot of great people — people who have made a difference and achieved unparalleled success in sports, business and other pursuits. None of them really caught fire until they took stock of themselves and became accountable. Some did this when they were young. Others didn’t face up to themselves until they were older. But in all cases they look back and say that being accountable to themselves is what changed their lives.

Richard Corder said personal accountability means always trying to be clear. When confronted with a problem, you can say, “I tried, but they wouldn’t let me,” he said, or you can say, “Can you help me figure this out? I need to get some clarity.”

It’s important to put some effort into establishing clarity, he said, offering me a quote from the inspirational speaker, Mark Victor Hansen: “By recording your dreams and goals on paper, you set in motion the process of becoming the person you most want to be.”

Listening to yourself can help you put your plan into action. I don’t know about you, but I have conversations with myself all the time, and from what I can gather from colleagues and friends, they do the same thing. This enables us to begin to develop a sense of our own accountability.

With accountability comes additional responsibility. For instance, in your job, do you speak up when you feel something could be improved? Or are you so concerned about the risk of falling out of favor that you don’t say anything?

In healthcare, we too often delude ourselves into accepting the status quo and are unwilling to try new things that just may be more efficient and guarantee a better experience for the patient. Accountability has to start with people who are willing to hold themselves to a higher standard and be answerable to themselves at all times. The goal is to never deviate from your dedication to excellence.

The road ahead is paved with uncertainty, and you will probably have to drive over many potholes along the way. The whole industry needs leaders who have the courage to look into the future with clear eyes and to inspire their people to do the same. We need to be willing to bring about the changes that healthcare so critically needs. It isn’t going to be easy. Those who hold themselves personally accountable to mission and vision and to themselves will be the stars that inspire all of us with their courage.

Richard Corder gave me a kind of motto for personal accountability. It’s all simple, two-letter words that go like this: “If it is to be, it is up to me.”

I have already put them up on my office wall.

Thanks again Chuck for the friendship, mentorship, interest, and support.

Numberless diverse acts of courage

Posted: July 31, 2014 Filed under: Health and Care Radicals, Heretic, Human error, Leadership, Learning, Safety | Tags: brave, Communication, culture of safety, Healthcare, hospital safety, Leadership, Lessons learned, patient safety, speaking up, taking risks, Telluride Summer Camp 3 CommentsYesterday afternoon the faculty and students at the “Telluride-East” Patient Safety Summer Camp visited Arlington National Cemetery.

As we paused for some reflections from our leaders Paul Levy and Dave Mayer I was overcome by the scale of what presented itself in the form of field upon field of white grave markers.

Poignant words reminded those gathered that we were indeed standing on hallowed ground and that many have given, and continue to give, the ultimate sacrifice. A sobering reality is that there are between 25 and 30 new burials every day at the cemetery.

Following our time of reflection I took a walk to reflect on the sacrifice, loss, and scale of what lay beneath me. 400,000 markers of lives once lived, now at rest.

In a recent piece of research published in the Journal of Patient Safety it is estimated that more than 400,000 hospital deaths are attributed to preventable harm. Put another way, since August 2013 more than 400,000 mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, sons and daughters are no longer alive as a result of harm that could have been prevented with better designed systems, more situational awareness, and other proven human factors and safety science approaches in health care.

I think these numbers are becoming “noise” for many leaders in healthcare, we have heard the numbers and yet still choose not to make the different decisions and the difficult choices. We disassociate from the difficult reality because we don’t “see” the totality of what we are doing.

The grave markers stopped me in my tracks, a visual reminder of what we are doing every year in healthcare by tolerating variation, blaming people, doing the same things over and over and expecting different outcomes.

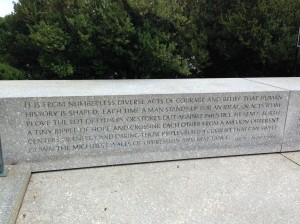

My walk took me to the Kennedy family grave site. Off to the side of the eternal flame is a Robert F. Kennedy quote that really resonated with the work we are doing with the faculty and students at Telluride-East:

It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

Robert F. Kennedy, South Africa, 1966

This quote captures what I will leave this time of learning and sharing with, and what I urge the students, residents and faculty to find the courage to continue doing…

- Lean in and keep speaking up to improve safety; these are the “numberless diverse acts of courage”

- Believe in yourself and the difference you can make

- Stand up for what you know is right and stand up for those less brave and courageous than yourself

- Speak up, even when your voice quivers and your hands shake. Speak up for patients, the ones you care for, know and for the one’s you dont…

- Most of all, send forth a “tiny ripple of hope”. These ripples will build to a current. These ripples will make care safer

- By thinking and acting differently, by bravely speaking up and taking a stand we will sweep down what often feels like a mighty wall

I commit to making ripples and I urge my new found colleagues and friends to do the same.

Make ripples. Ripples save lives, ripples make care safer.

You promote what you permit

Posted: July 25, 2014 Filed under: Disruptive Behavior, Health and Care Radicals, Heretic, Leadership, Patient Experience, Safety, Workplace Culture | Tags: brave, culture of safety, Healthcare, Leadership, speaking up 1 CommentI recently spent a day with a number of senior clinicians all working in an environment that is permitting pockets of disruptive, unprofessional, and quite frankly dangerous behavior amongst caregivers. The last conversation of the day ended with a chilling reminder that we still have much to do, “The problem is that for too long, to be successful in academic medicine, you haven’t needed to be polite, professional and well mannered…”

Last night I read a headline that really grabbed my attention…

Why disruptive docs may not be so bad after all

Here was my reply:

I will start by saying that there is, in my mind, absolutely no place whatsoever for a disruptive (rude, hostile, ill-mannered, bad tempered) anyone in a safe, efficient, patient centered, healthy, just healthcare environment. Let’s not limit this to physicians…

I am sick and tired of hearing that being a technically excellent clinician and being a decent, respectful, polite human being are somehow mutually exclusive. They are not, and to suggest otherwise is disrespectful to the enormous number that are.

Please don’t suggest that organizations committed to improving the experience of those they serve are “getting rid of disruptive docs…” as an approach because they now have dollars tied to HCAHPS performance. This is a gross over simplification.

I’d offer that any healthcare organization that hires and retains mean, disruptive physicians (or anyone else) is complicit in creating a dangerous, un-just, unreliable work environment, not simply a less than ideal patient experience.

We need to start changing the conversation, raising our standards and expectations, and demanding more of one another. A world class, safe, reliable, effective experience is within our reach, but only if we stop confusing experience with “nice” and start holding ourselves and our colleagues to not only the highest technical standards but also high behavior standards.

I understand that we need to be mindful of the words we use, and am enthusiastically open to the idea that we need to lead with more “healthy innovative disruption” as we work to improve the safety and delivery of health and care. (Note the great work done by Helen Bevan and colleagues at the NHS with the notion of being a rebellious health and care change agent). But to suggest that disruptive behavior, in the way this article does, is somehow OK, and furthermore actually has a place in our healthcare environment, is reprehensible.

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Language and the Words We Choose

Posted: June 17, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Communication, Don Berwick, Healthcare, Leadership, Telluride Summer Camp Leave a comment Our language, the words we use when we use them, our inflection, emphasis, and our body language are all critical elements of building and leading a safe culture – so too are the feedback loops necessary to keep us honest.

Our language, the words we use when we use them, our inflection, emphasis, and our body language are all critical elements of building and leading a safe culture – so too are the feedback loops necessary to keep us honest.

I recently read the transcript of Don Berwick’s 2010 Yale Medical School graduation speech as case study preparation for this year’s Patient Safety Summer Camp in Telluride. One of the most poignant aspects of his speech for me, is the reminder of the power of the words we choose. Don reflects on a patient’s wife hearing the word ‘visitor’ as a label to identify her when visiting her sick husband. Don asks us to reconsider this, to change our mindsets, to think differently.

Don invites us to make a personally accountable choice to consider that it is us, physicians, nurses, housekeepers, technicians, the entire care team – that are in fact the real ‘visitors’ in the lives of those we care for. Think about it – the husband, wife, partner, lover, friend, child, sibling they are the relationships, the rocks, the memories and also, in many cases, the caregivers. Think about how they want to spend time with their dying or sick family member, what do they need? What do they want to talk about? We must remember that we are indeed the visitors in the lives that we are fortunate enough to care for.

The students and faculty at this year’s roundtable have been using different words, and have been open to hearing feedback regarding their mindsets around language and the words they use. I spoke at a recent company meeting about feedback and how we can choose to think of it as either a tennis ball or gift. If the former, it comes at us fast, it could hurt, and we are naturally inclined to want to immediately hit it back. Thinking of feedback as a gift changes our perspective–if done right it’s packaged well, we can take it with us and open it when we want, and it’s ours to do with as we please (keep or discard…)

Watching the #TPSER10 faculty modeling openness to feedback and hearing the tough messages, and hearing the students give and ask for feedback is eye-opening and refreshing. John Nance reminded us that some element of communication failure is behind almost every sentinel event and serious safety event.

Our language, our words, our ability to ask for and receive feedback help us communicate better. Ask for feedback about your language and the words you are using, and then keep the gift…